Read about the life of Shirley S. Abrahamson, or click here to visit the Visual Biography and explore her life in pictures.

Early Years

Shirley Schlanger Abrahamson was born in the Bronx, New York, on Dec. 17, 1933, to parents Leo Schlanger and Ceil Sauerteig, both Jewish immigrants from Poland.

She grew up in New York and for a time in New Jersey, where her parents ran a grocery store. As a small child, Shirley often said that she wanted to be President of the United States. By the time she was six, her career plans changed. She decided to become a lawyer. Her parents never discouraged her. At least now she was being realistic.

At age 12, Abrahamson enrolled in Hunter College High School. She met her future husband, Seymour Abrahamson, while the two worked at a summer camp. After graduating from high school in 1950, she attended New York University where she majored in political science and minored in English literature. She graduated in three years and married Seymour in the summer of 1953 at age 19.

At the time, Seymour was working on his Ph.D. in genetics with Nobel Laureate H.J. Muller at Indiana University. After their wedding, Abrahamson began her legal studies at Indiana University Law School. When she graduated valedictorian in 1956, she was the only woman in her class. The law school’s dean apologetically advised her that unless she wanted to be a librarian, the prestigious Indianapolis law firms would not offer her a position because she was a woman.

The Abrahamsons had other plans. They headed to the University of Wisconsin-Madison. There, Seymour did a year of postdoctoral work, and Abrahamson started her doctorate with Professor Willard Hurst, the founder of the modern field of American legal history. The Abrahamsons worked in New York and New Jersey for several years before returning to Madison where Seymour received a professorship in zoology and genetics at the University of Wisconsin.

Legal Career

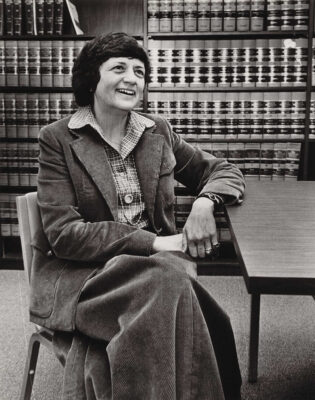

Shirley Abrahamson finished her doctorate on the history of the Wisconsin dairy industry and was admitted to the Wisconsin Bar in 1962. There were few women lawyers in Madison then, and most were employed by the government. A handful of these women practiced solo or in law firms with their husbands or fathers. Abrahamson was the first woman hired by a private firm in Madison—LaFollette, Sinykin, Doyle & Anderson.

She developed an expertise in tax law and taught the subject at the University of Wisconsin Law School. By the end of her first year, she became a partner of the firm. The following year, she gave birth to a son, Daniel N. Abrahamson. While at LaFollette, she headed the Madison office of the Wisconsin Civil Liberties Union. She also served on the Mayor’s Commission on Human Rights and helped write Madison’s fair-housing ordinance—the first fair-housing law in Wisconsin.

In 1965 Abrahamson and Assistant Attorney General Betty Brown became the first two women to oppose each in an oral argument before the Wisconsin Supreme Court. The case was State v. Strickland, 27 Wis. 2d 623, 135 N.W.2d 295.

The University of Wisconsin Law School offered Abrahamson a professorship in tax law in 1966. She accepted on the condition that she would come in as a tenured professor and that her colleague and friend, Assistant Professor Margo Melli, would also receive tenure. The two became the first tenured female professors at the law school.

Despite the extraordinarily heavy workload, Abrahamson loved teaching and practicing law so much, she continued to do both for the next 10 years.

Judicial Career

In 1976 Gov. Patrick Lucey changed the course of Wisconsin history when he appointed Shirley Abrahamson the first woman to serve on the Wisconsin Supreme Court. People jammed the Assembly chambers of the Capitol to witness her swearing in.

Abrahamson’s legendary work ethic continued during her time as a justice. The year she joined the court, each justice wrote close to 40 majority opinions, but she wrote an additional 17 concurring and dissenting opinions. Soon she began traveling around the state to educate the public about the justice system, the least understood branch of government. She advocated for the Wisconsin Supreme Court to hold oral argument in distant parts of the state so that more residents had an opportunity to observe the justices in action. In 1993, the supreme court held argument outside of Madison for the first time in its history. The program became known as “Justice on Wheels.”

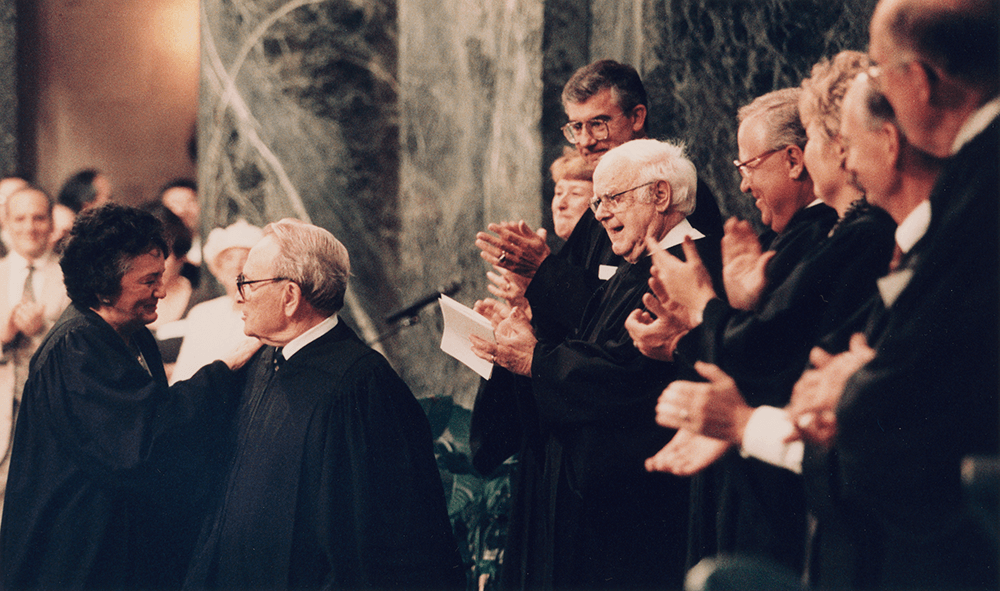

In 1996 Abrahamson assumed the position of chief justice of the Wisconsin Supreme Court based on her seniority, the first woman to hold this position in Wisconsin’s history. William Rehnquist, a Wisconsin native and chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, administered her oath in the Capitol rotunda before 1,200 admirers. Abrahamson told the audience, “To ensure a truly just legal system, one that reflects the history and hopes of this state, there must be greater public participation in the justice system.” She vowed to get the public more involved in the courts.

She kept her promise. To promote public confidence in the judicial system, she continued the “Justice on Wheels” program. She also developed “Court with Class,” an award-winning program that brings high school students to the Capitol in Madison to observe an oral argument and meet with a justice to learn how appeals are decided. Because the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s administrative decisions have a profound effect on people and the courts, she supported allowing the public to observe the justices debating and making those decisions. The Wisconsin Supreme Court was the first state supreme court to do so.

During her tenure as chief justice, Abrahamson served as president of the National Conference of Chief Justices, chair of the board of directors of the National Center for State Courts, and chair of the National Institute of Justice’s National Commission on the Future of DNA Evidence.

Her tireless efforts to demystify the judicial system garnered her many national awards such as the American Judicature Society’s inaugural Dwight D. Opperman Award for Judicial Excellence; the National Center for State Courts’ Harry L. Carrico Award for Judicial Innovation for serving as a national leader in safeguarding judicial independence, improving inter-branch relations, and expanding outreach to the public; and the American Bar Association’s John Marshall Award in recognition of her dedication to improving the administration of justice.

Following an amendment to the Wisconsin Constitution, Abrahamson resumed her position as justice in 2015. In 2018 she announced that she had been diagnosed with cancer and would not run for reelection in 2019. By then she had set a Wisconsin record—she had been opposed in four straight elections and in each election won at least 55% percent of the vote.

Shirley Abrahamson passed away on Dec. 19, 2020, at age 87. She had served as a justice of the Wisconsin Supreme Court for 43 years—longer than any other justice in Wisconsin history.

Photo credits: Abrahamson in court: Wisconsin Historical Society ID 149705; Abrahamson at retirement: Amber Arnold, Wisconsin State Journal; other photos: from Daniel N. Abrahamson.